Burning Tokens

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to determine the limits of the newest LLMs. So here’s my latest test: what’s the best “one-prompt chess engine” I can come up with. Maybe I can even spur others into a contest—could be fun. And of course the question follows: what’s the best engine I can develop purely with vibe-coding? And what do I learn in the process?

Every beginning is hard

I’ll admit it: I’m too lazy to install GCC or a JDK to get a really fast engine. It’s only meant to be an experiment. Unsure whether JavaScript or Python is the better alternative, I have the bad idea of letting the AI choose. So in the prompt I ask it to take a thorough look at the task—writing a chess engine—then decide which of the two languages is more suitable, and then get started.

And I write the sentence: “I will publish the results. Be your best”.

Was it the stress of publication? The overwhelm of choosing a language? Who knows—anyway, Cursor + Opus 4.6 is overwhelmed, burns tokens for an hour worth $8, until I cancel. Aside from a partly incoherent thought process, no result.

Every easy beginning is easy

This time I start with the combination of VS Code, GitHub Copilot, and Cline, with Claude Opus 4.5 running underneath. I begin with a simple prompt for a simple engine. And I set Python as the language in advance.

And after not much time at all I have a simple engine that can do alpha-beta with iterative deepening and plays chess quite decently. Yes, with 5–10 seconds of thinking time it only thinks 4 plies ahead, but still. I’m happy with the result.

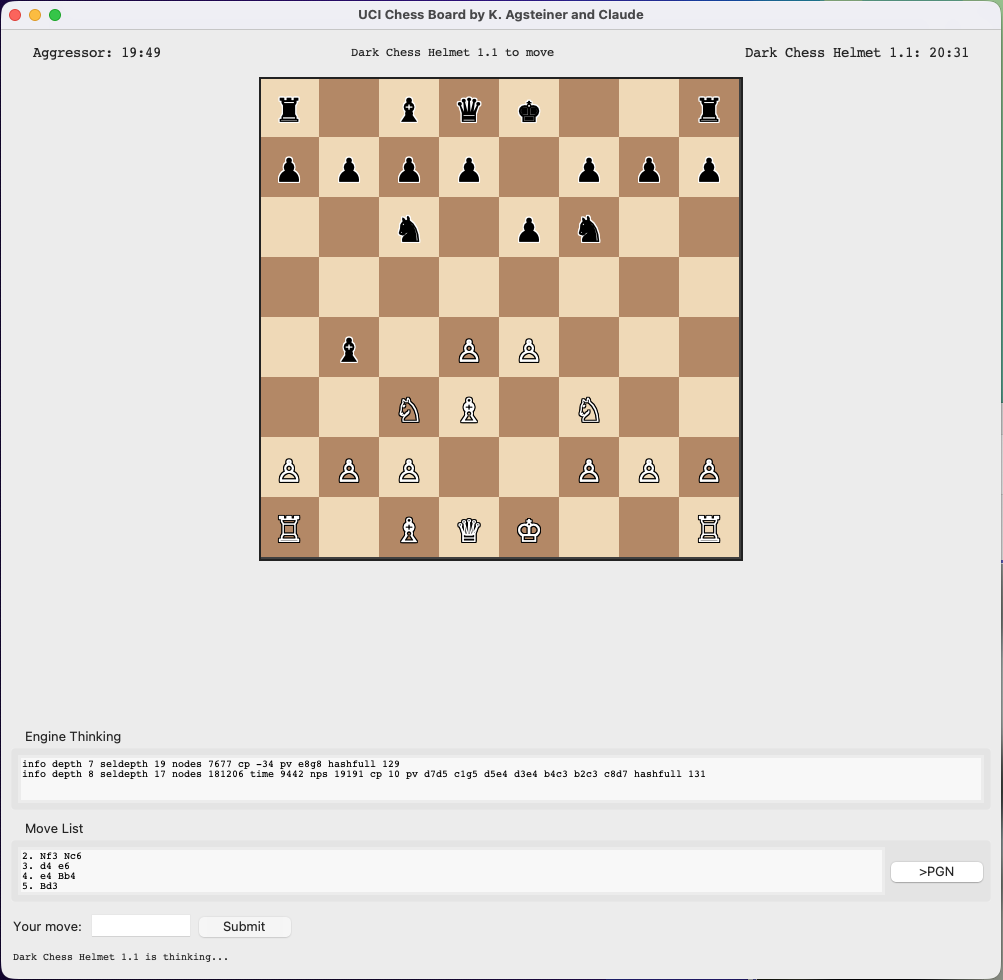

In parallel, the engine builds me a simple chess UI to play as a human against engines or to run engine matches. Since my engine has to be started with python engine.py, I can’t use real chess UIs for it. A few iterations later (an ASCII board is really unreadable) I have this:

How far can you go?

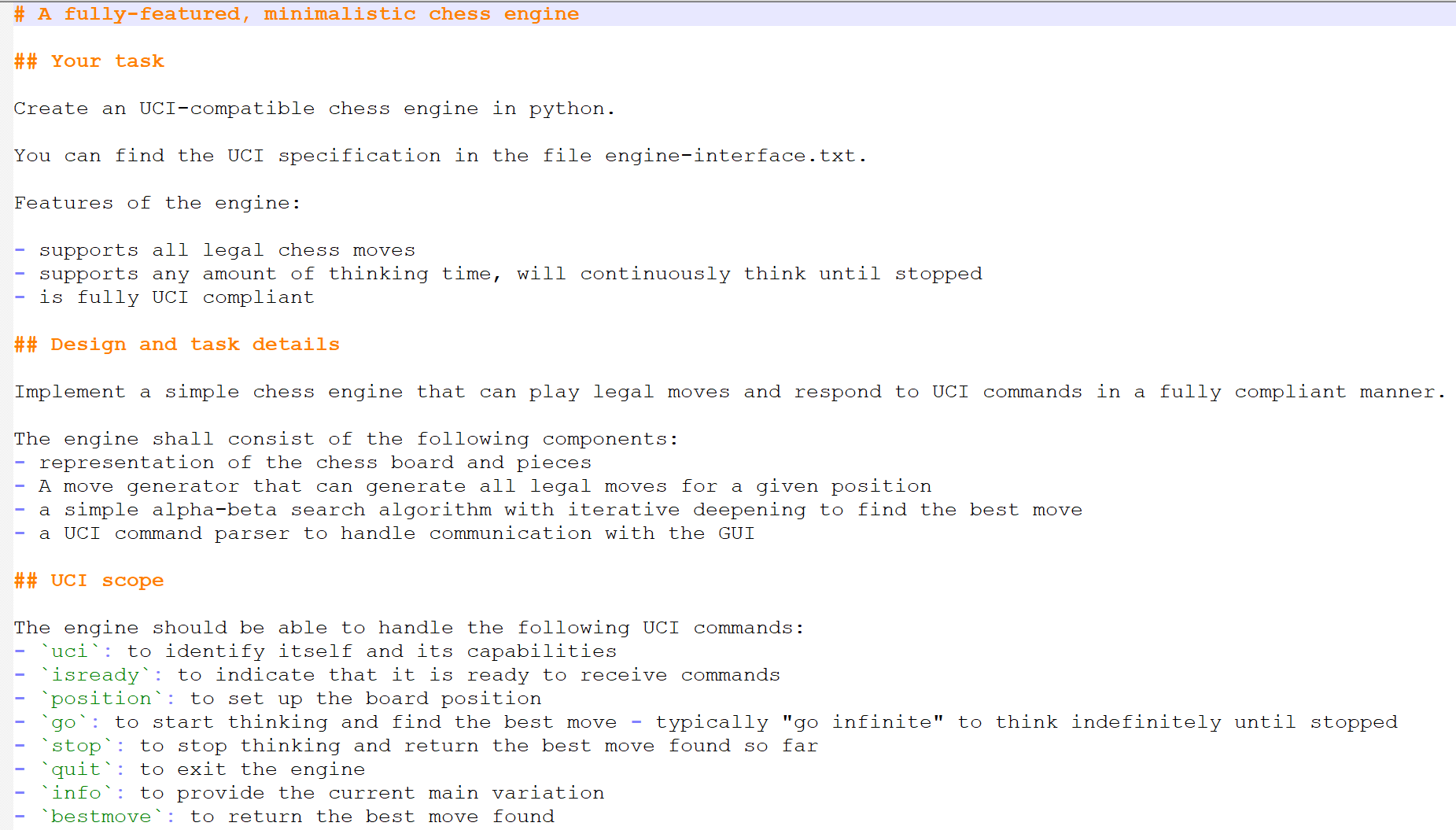

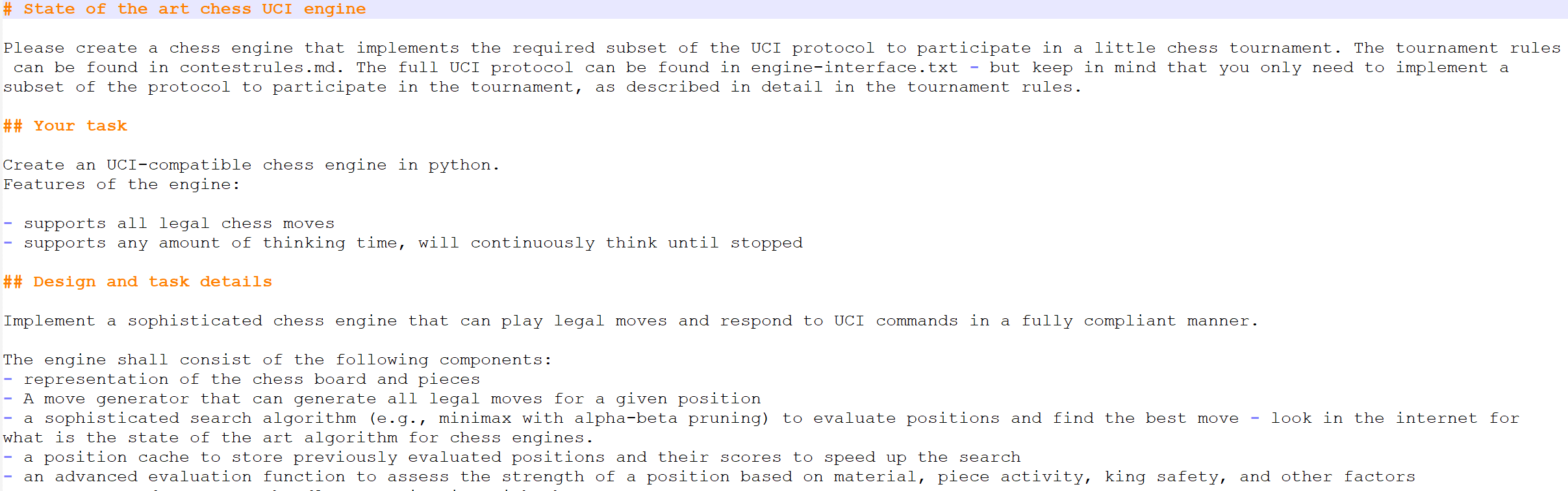

The next prompt is my first attempt to have it write a strong-playing engine:

The result is impressive. In normal positions it gets to 10,000 analyzed positions per second, usually reaches 8-ply + 15 selective, and overall plays quite decent chess. However, it has no idea about openings and likes to move the knights stupidly around the board instead of developing pieces or fighting for the center. Similarly, it has no idea about endgames—and if a pawn is on the 3rd rank, at least 10 plies away from promotion, then the engine doesn’t get the idea to push that pawn.

Improvement through further prompts

So tell the engine it should add analyses for center control, piece mobility, development in the opening, and in the endgame king centralization and advanced pawns.

I feel like Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, who explained the mountains of India and the milk of cows to the drinks AI that initially produced something “almost, but not quite, entirely unlike tea”. Whereupon the machine, with enormous computational effort, produced tea.

Because after my explanations and the AI’s improvements, the engine plays chess. I didn’t measure the ELO values, but I’d estimate it at around 1800 ELO. No stupid blunders, sometimes strategically clumsy, sometimes very forceful.

And then came what blew me away. Why I’m also writing this longish text for you, dear reader.

Performance tuning

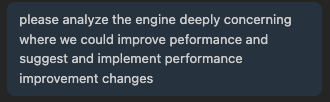

I wanted to know: can an LLM independently performance-optimize something non-trivial like a chess engine?

So I prompted:

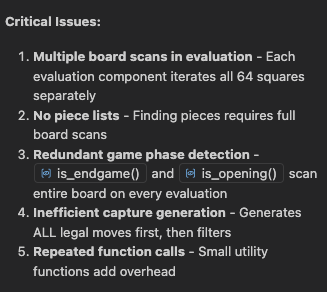

Whereupon the AI, after pondering for a few minutes, replied:

Those are pretty impressive insights. I wouldn’t dare do point 1; it also has the potential to make the code more complicated for little performance, but the other points are extremely valid insights into how the engine works.

The LLM then tinkered for about 15 minutes and declared the performance problems solved.

Ran it. After one line of info output the engine hung. So I told the LLM about it, conveyed my theory that the problem was probably due to switching to a new iteration (which turned out to be completely wrong). The LLM gets going, writes a series of test scripts to narrow down the error. My task: skim the test scripts, click OK.

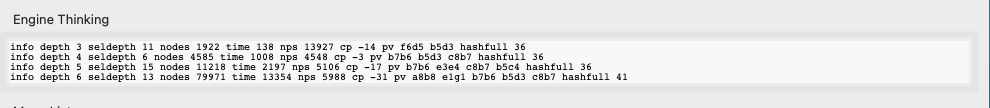

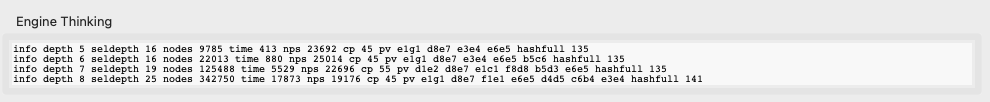

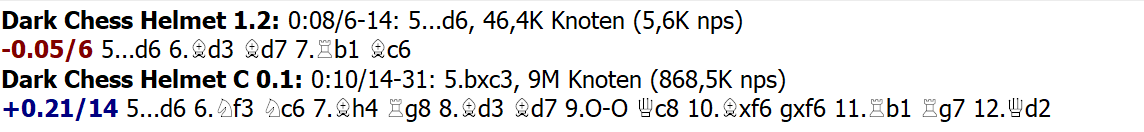

The astonishing part: with this approach—no debugging, just writing scripts, observing behavior, looking at code—the LLM figured out after 10 minutes that the bug lies in undoing en passant moves. Fixed the bug. I (in disbelief) start the engine and everything works. And in a game against the previous version:

Before: The engine analyzes about 5000 positions per second. Not bad.

After: The engine analyzes about 20000 positions per second. Overall the improvement is somewhere between factor 2 and 4, depending on the position.

State of shock

I had a comfortable worldview: AIs can generate good new code, but refactoring—especially of something non-trivial—that’s something for humans, the AI can’t do that yet. Accordingly, I’m impressed that a piece of software that is rather small in terms of number of lines (about 3000 lines), but one of high algorithmic complexity, was cleanly analyzed for weaknesses by the AI and significantly improved independently through major rebuilds.

That can make you a little afraid for the future of your own profession.

But that wasn’t the most astonishing insight of the day.

The move

Working on a chess engine can have something addictive about it—you iteratively improve the position evaluation, try more aggressive lines, let the older one play against the newer one, etc. At some point I left my self-written test environment and (thanks to a small script) moved into HIARCS Chess Explorer as an engine, competing against—ELO-limited—real engines. Over time I learned that the AI-written engine is around 1600 ELO. Not bad. My level, on a good day.

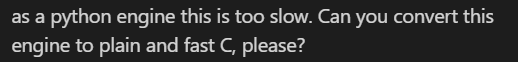

Now, Python is interpreted, and not blazing fast, not ideal for the number crunching of a chess engine. So for the next task this time, Cursor + ChatGPT 5.3 codex had to step in:

Did it work? On the first try, rather mediocre—the first engine left out half the functionality—less complex search, less complex analysis, errors in the UCI implementation. But after about 5 more prompts I had an implementation of the engine in native C.

And wow is Python snail-slow.

I had expected a factor somewhere between 10 and 20. But 200? Where the Python engine thinks 6 plies ahead, it manages 14 in C, and instead of 5,000 positions per second a million.

In ELO terms the engine should be around 2200–2400. That’s far from what good engines achieve, but for an engine vibed together with about 4 hours of work, quite respectable. And I can chalk up another engine under “too strong for me”.

The moral of the story

First: A chess engine is not the test with which you can push today’s LLMs to their limits. Sure, 3000 lines fit into an LLM’s context 30 times over today. What is a lot for a human with 40 pages of source code, and what would have overflowed ChatGPT 3.5’s 16K context back then, is simply small at a million tokens.

Second: Modern agent environments with modern LLMs underneath also have no problems with big refactoring on projects like this, with conversion into a very different programming language.

And third: I thought for a long time about what it means when an LLM simply writes down a fairly complicated search algorithm. Is it that smart? Did it just see 100 chess programs on GitHub and copy them down? But is there even anyone else as dumb as I am and writes chess in Python? I’m not a proponent of the plagiarism theory—I got all my computer science knowledge from humanity’s store of knowledge and didn’t pay a cent for it (universities in Germany are almost free). I benefited from knowledge on Stack Overflow, acquired knowledge from it. Why should it be reprehensible if not I, but an artificial intelligence does the same?

For me it’s about measuring real programming competence. Knowing an algorithm by heart and writing it down with slight adjustments requires no intelligence. On the other hand, my wishes for an improvement of the position analysis were implemented correctly and cleanly. If the machine only copied and didn’t understand what it wrote, that would be impossible.

It remains difficult. What’s the next problem to test LLMs? One that’s big enough for them?

(Teaser: it’s GECODE (which I deal with professionally)).